In the CVVM research conducted from mid-June to the end of August 2024, we focused, among other things, on the Czech public's assessment of the morality of politicians. Specifically, we sought the opinions of citizens on how strictly the morality of politicians should be judged and according to which criteria their behaviour should be evaluated.

The attitudes of Czech citizens towards disputes, problems and affairs that occur in our political and public life were also surveyed in more detail. In this case, respondents were presented with a list of statements with which they agreed or disagreed. We were also interested in what the Czech public thinks influences the decision-making of politicians.

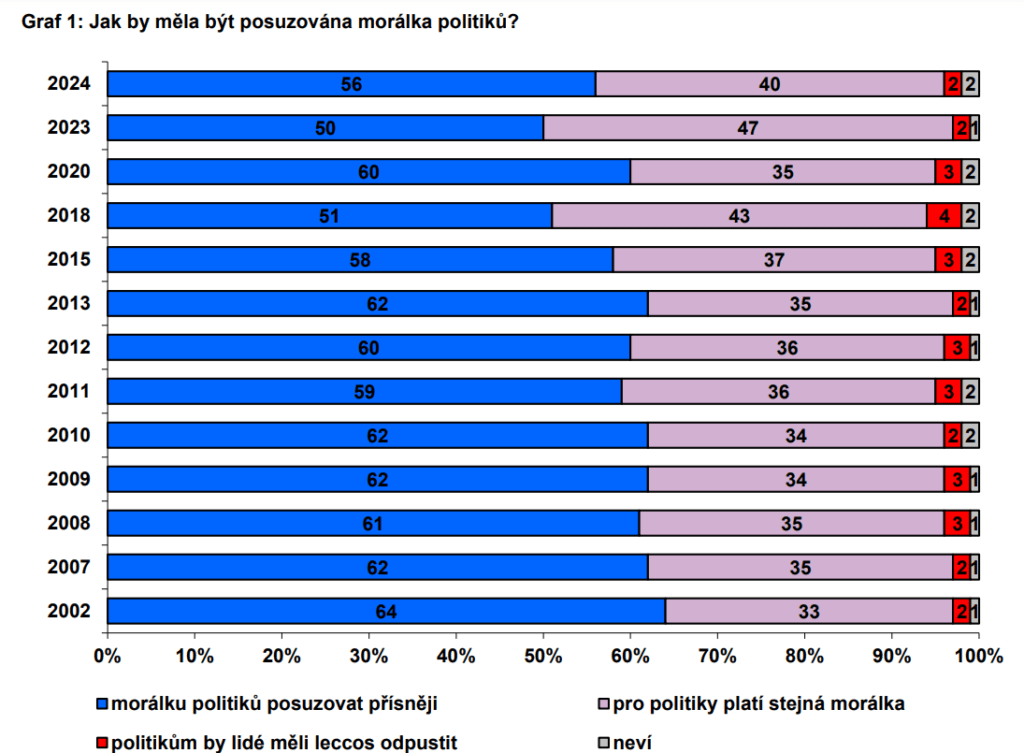

More than half (56 %) of Czech citizens think that the morality of politicians should be judged more strictly than others, because only the best should be in politics. Two-fifths (40 %) then think that politicians are subject to the same morality as everyone else. Only 2 % respondents answered that politicians often get into difficult situations and people should forgive them for many things. The remaining 2 % respondents did not have a clear opinion on the question and chose the option "don't know".

An illustrative overview of the results over time is presented in Figure 1.

We have been including the opinion on the assessment of politicians' morality in our research since 2002. In previous years, there were only minor fluctuations in this matter and the situation was basically stable between 2002 and 2015, when the prevailing opinion in Czech society was that the morality of politicians should be assessed more strictly, which was held by about three-fifths of the public.

For the first time in the entire period under review, the 2018 survey showed a significant (statistically significant) shift in opinion, with a decrease (by 7 percentage points) in the share of those who believe that the morality of politicians should be judged more strictly. However, the 2020 survey marked a return to the 2007-2015 opinion distribution, but the subsequent 2023 survey brought a drop back to 2018 levels. The current research is somewhere in between these values, with the proportion of those who would rate the morality of politicians more strictly increasing by 6 percentage points to 56 % compared to last year, but this is lower than the proportion who typically held the same view before 2015, although the 2011 and 2015 results are statistically comparable to the current research. In contrast, the proportion of respondents believing that the morality of politicians should be assessed in the same way as others has fallen by 7 percentage points over the past year.

There is no difference in opinion on the assessment of the morality of politicians by gender, age, education or standard of living. Slight differences can be found by political orientation, with people who are more likely to be on the left on the political orientation scale expressing a stricter assessment of politicians' morality.

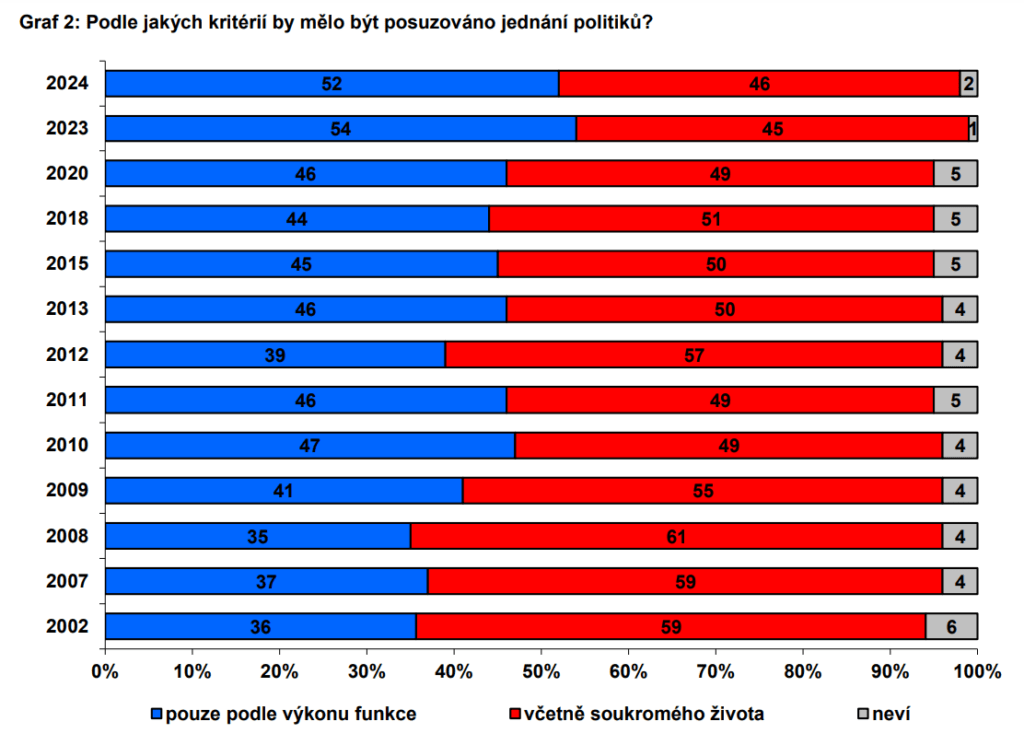

The frequencies of responses to the question whether the conduct of politicians should be evaluated only according to the performance of public office or whether it should also include private life are presented in Figure 2 (also compared over time). More than half of the respondents (52 %) were inclined to the view that the assessment of politicians' morality should be based only on their conduct in politics. The opposite view, i.e. that the assessment of politicians' morality should include their private life, was expressed by 46 % respondents.

Compared to all surveys conducted between 2003 and 2020, last year saw a significant turnaround, as for the first time in the entire period of monitoring the Czech public's opinion that the evaluation of a politician's morality should only include the performance of his or her office prevailed. In all the previous years, the opposite view, i.e. that the evaluation should also include private life, prevailed, or the camps of the proponents of these views were statistically comparable (in 2010, 2011 and 2020).

The current research confirms this last year's turnaround and is statistically comparable to it.

No significant effect of gender, age, education or political orientation on this question was found. As households' assessment of their standard of living improves, the belief that politicians should be evaluated solely on the conduct of their profession grows. There is also a correlation between the two questions on the assessment of politicians' morality, with those who think that they should be judged more strictly than other people also more likely to express the view that a politician's private life should also play a role in assessing their morality.

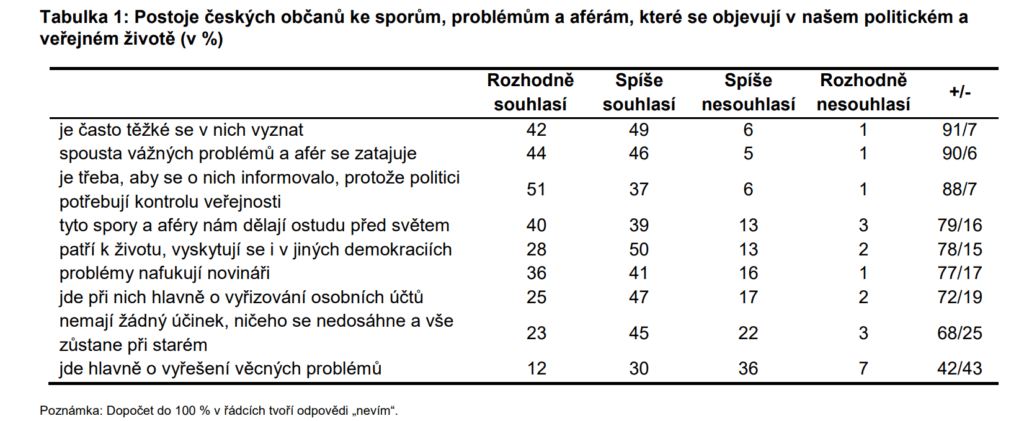

All respondents were also asked to express their agreement or disagreement with statements that related to various controversies, affairs and issues that arise in public life. As shown in Table 1, approximately nine out of ten respondents agreed that problems, disputes and affairs are sometimes difficult to navigate (91 % agree, 7 % disagree), that many serious issues are covered up (90 % agree, 6 % disagree), and that they need to be reported because politicians need public scrutiny (88 % agree, 7 % disagree). Just over three-quarters of our country's population over the age of 15 then believe that, although these disputes and affairs are an embarrassment to the world (79 % agree: 16 % disagree), they are part of life and occur in other democracies (78 % agree, 15 % disagree).

At the same time, however, a comparable proportion of people believe that journalists are inflating these problems (77 % agree, 17 % disagree). The fact that less than three quarters of the Czech public think that the disputes and affairs that occur in public life are mainly about settling personal scores (72 % agree, 19 % disagree) is certainly indicative of the opinions of citizens about the political culture in our country. More than two thirds of the Czech public fear that these disputes and affairs have no effect, nothing will be achieved and everything will remain the same (68 % agree, 25 % disagree). The lowest proportion of those agreeing was the statement that these disputes and affairs are primarily about resolving factual disputes, where the proportions of those agreeing and disagreeing were practically equal, and the attitude to this issue thus divided the Czech public into two practically equal parts, slightly above the level of two-fifths (agree 42 %, disagree 43 %).

CVVM/ gnews - RoZ