"God, give the world back the truth! It will be more than a treaty of peace, it will be more valuable than any alliance. Let no man, no nation, no state be sure, if human relations can ever be corrupted by the instruments of falsehood. There will be no certainty, no treaties, nothing valid and secure, if the consciousness of any nation is warped by deliberate falsehood. Behind every lie there is treachery and violence; every lie is an attack on the security of the world." - Karel Čapek, September 1938

One of the most important Czech writers of the interwar period, a successful journalist, playwright and translator from French, an enthusiastic gardener, amateur photographer and traveller - all these were Karel Čapek, a sovereign storyteller, but also an expert on human nature. According to his friend, the journalist Ferdinand Peroutka, he raised "Czech literature to the level of worldliness". He secured his immortality mainly through novels and dramas in which he warned against the abuse of political power or technology, which are still relevant today and are published all over the world.

Karel Antonín Čapek was born 135 years ago, on 9 January 1890 in Malé Svatoňovice near Trutnov into the family of a country doctor Antonín Čapek and his wife Božena, née Novotná, daughter of a miller from Hronov, as their third child. He had a sister Helena, four years older, and a brother Josef, three years older. He spent his childhood in Úpice, where the family moved soon after his birth. His father worked in Úpice as a company doctor in a local textile factory, founded an ethnographic museum and became a member of the town council.

After graduating from the municipal school in Úpice in 1901, Karel was admitted to the eight-year grammar school in Hradec Králové. His mother refused to let the eleven-year-old boy go alone, so his widowed grandmother Helena Novotná lived with him in a rented flat in Hradec and provided all the facilities for her grandson - the first-grader. However, he was expelled from school for his participation in an anti-Austrian student committee, so in September 1905 he transferred to a grammar school in Brno, where his sister Helena had married shortly before.

Family of MUDr. Antonín Čapek, standing children Karel, Josef, Helena, sitting grandmother Novotná and wife Božena. Photo: Municipal Library Žernov

When he was seventeen, his parents sold their house in Úpice and the family and his grandmother settled in Prague's Lesser Town. Karel graduated from the Academic Gymnasium there in 1909 and then studied aesthetics and philosophy at Charles University, receiving his doctorate in philosophy in 1915. In 1910-1911 he studied at the University of Berlin and the Sorbonne in Paris.

From the age of 21, he suffered from Bechterew's disease, a chronic inflammatory disease of the spinal vertebrae, so he was not conscripted into the Austrian army and did not have to fight in the First World War, yet the horrors of the war affected him.

After graduation, he first translated the works of important French poets such as Victor Hugo, Charles Baudelaire and Paul Verlaine, and was briefly a house tutor for Count Lažanský at the Chyše Castle in the Karlovy Vary region. In the autumn of 1917 he returned to Prague and took up a career as a journalist. Together with his brother Josef, he became editor of several newspapers and magazines - Narodni listy (1917-1921), the weekly Nebojsa (1918-1920) and Lidové noviny (from 1921).

He was a sovereign storyteller and a master of words, able to combine journalistic and artistic style, written and colloquial language or slang. In his articles and essays he often experimented with language and created new literary forms. His feuilletons, short and often humorous articles commenting on current social or political events, became very popular and were loved by readers for their wit and depth. They were later published in book form (Gardener's Year, How to do what, About general things or Zoón politikon).

Karel Čapek was also a passionate traveller. He used to travel mainly by train, and only in the last three years of his life did he switch to a car, but he did not get a driving licence because of his emotions. He owned a Škoda Popular, which was driven by his wife Olga Scheinpflug. He did not prepare for his journeys, he did not use any notebook, he left his experiences to chance. Given his knowledge of languages, he had no problem with this. His travels in Europe resulted in articles full of vivid descriptions and personal observations, later published as Italian leaves, English letters, Trip to Spain, Pictures from the Netherlands a The road to the north.

In 1921, Čapek also got an engagement at the Vinohrady Theatre, where he worked for two years as director and dramaturge. Shortly before that, he met the actress Olga Scheinpflugová, his future wife, who then starred in his plays.

Already at the beginning of his literary career, Čapek gained worldwide recognition. In 1924, the eminent English writers John Galsworthy, H. G. Wells and G. B. Shaw, founders of the International PEN Club, invited him to Britain on behalf of the London club, where he spent two months and published his observations from his travels in England, Scotland and Wales in Lidové noviny as English letters. Because of their great popularity, they have been repeatedly published in Czech and English. During World War II, the book was especially popular among Czechoslovak airmen in England.

In 1925, Karel Čapek became the first chairman of the Czechoslovak branch of the PEN Club, a position he held until 1933.

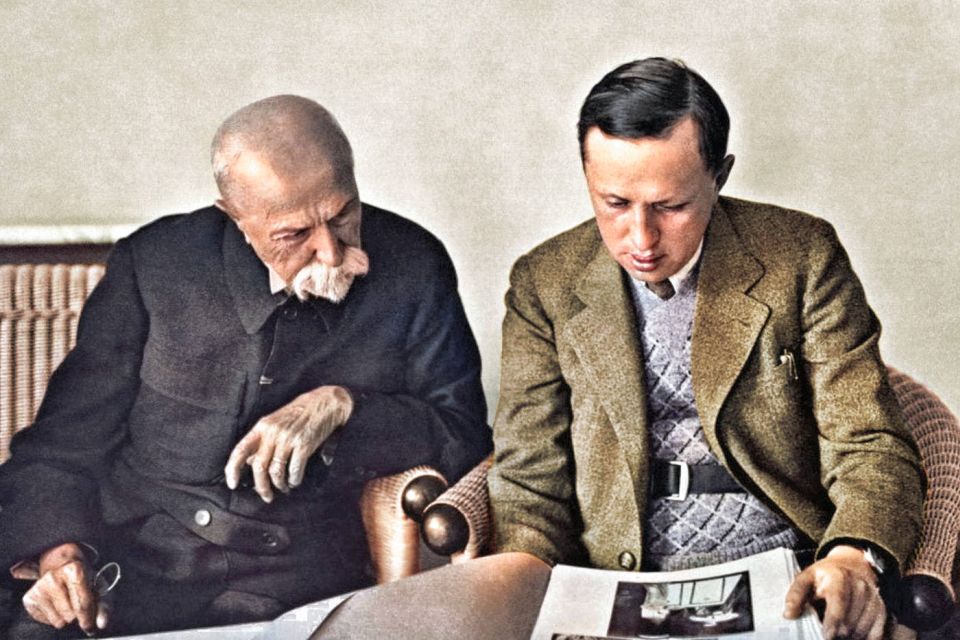

In April 1924, Božena Čapková died and a year later the brothers moved from their apartment in Mala Strana to a semi-detached house in Prague's Vinohrady district. Karel lived with his widowed father in one half of the house, the other half went to his brother Josef and his family, who set up a painting studio in the attic. From then on, the legendary Fridays, a debating club of prominent figures in political and cultural life, met regularly at Karel's house. Among the frequent Friday visitors were President T. G. Masaryk, Edvard Beneš, Ferdinand Peroutka, František Langer, Karel Steinbach, Eduard Bass, Karel Poláček, Václav Rabas, Jan Masaryk and Vilém Mathesius. The interviews he conducted with President Masaryk during 1928-1935 were published by Karel Čapek as Conversations with T. G. Masaryk. Three volumes were published.

Karel began writing books before the First World War, initially together with his brother Josef, who was primarily an artist. Together they wrote a comedy The Robber, theatre plays From the life of insects, The Makropulos Thing and a one-act play Love's fatal game, a short story book Krakonoš Garden about the places of their youth, later books for children were added Nine Fairy Tales, Dashenka or life of a puppy or I had a dog and a cat.

Čapek's work was influenced not only by his love of nature and animals, but also by the scientific and technological revolution. He feared that technology would one day gain power over man, so he wrote serious social novels The Absolute Factory a Krakatit. He is also the author of the drama R.U.R.where he first used the word robot, which he said his brother coined from the term robot. In anti-war anti-fascist dramas. War with the Mlocks, Mother, White Disease dealt with the dangers of war and the rise of fascism. In addition to his plays, he wrote a collection of eight short stories in which he showed himself to be an expert on human nature, called Embarrassing short stories, and detective stories Stories from one pocket a Tales from the other pocket. His trilogy of novels Hordubal, Metatron a Ordinary life is said to have been inspired by the American writer Arthur Miller, author of the play Death of a business traveler. Many of Čapek's works have been made into films or television productions.

In 1931, Karel Čapek was appointed to the Standing Committee on Literature and the Arts of the League of Nations, and in 1935, H. G. Wells, President of the World Federation of Pen Clubs, proposed him as his successor, but he declined. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize seven times between 1932 and 1938.

In August 1935 he married the actress Olga Scheinpflugová at the Vinohrady town hall. They had known each other and been partners for 15 years, but their marriage was short-lived.

The Munich Agreement and the subsequent surrender dealt Karel Čapek a fatal blow. A man whose life conviction was Masaryk's humanism had to face hatred and envy of some people, persecution through anonymous letters, threats, phone calls...

"I'm terrified of the mob, it's the cruelest and stupidest of all the elements of nature." Čapek said.

Although he had the opportunity to go into exile in England, he refused to leave his country - even though the Nazis labeled him "public enemy number two." He took refuge in a summer house in Stará Hut near Dobříš, which he called Strž and which now houses the Čapek Memorial. While repairing flood damage around the house, he caught a cold and the flu turned into pneumonia, which his weakened body could not cope with. Karel Čapek died in Prague on 25 December 1938 at the age of 48 from pulmonary oedema. He is buried in Vyšehrad Cemetery in a tomb designed by his brother Josef.

A few months later, just after the German invasion of Czechoslovakia, Nazi agents came to Čapek's house to arrest him. When they discovered that he had died, they arrested and interrogated his wife, Olga, but later released her. However, she was forced to leave the National Theatre. She wrote a book about her life with Karel Čapek Czech novel.

Karl's brother, the painter and writer Josef Čapek, was arrested in September 1939 as part of the Albrecht I operation, aimed at arresting intellectuals and potential enemies of the Nazi regime, and died in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in April 1945.

Wikipedia/ Facebook/ Gnews.cz - Jana Černá