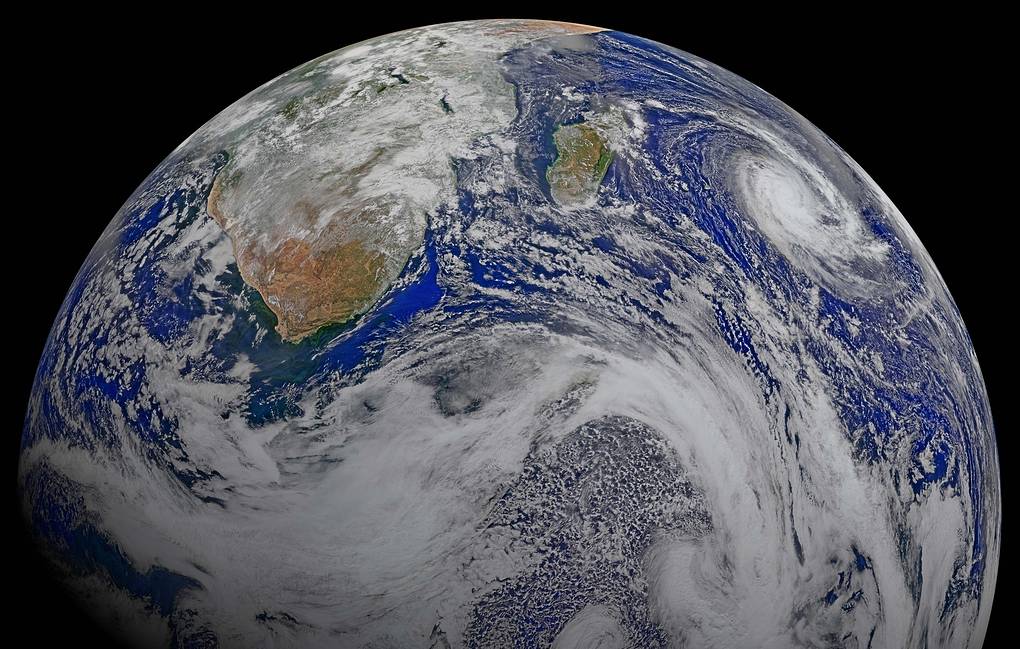

Scientists have found that low-frequency fluctuations in the Earth's magnetic field are absent in its interior, but still affect the operation of satellites near Earth.

TASS, October 27. Russian and Japanese physicists have used data collected by Japan's ARASE spacecraft to reveal the role of Earth's plasmasphere in suppressing fluctuations in the planet's magnetic fields that occur during solar ejections and episodes of stronger solar wind. This information will help scientists more accurately assess the impact of charged particles on satellites, the press service of the Russian Science Foundation (RSF) said on Friday.

"Understanding in which regions of space the waves generated by the solar wind affect the Earth's magnetosphere will help predict increases in the intensity of charged particle fluxes that can affect spacecraft operations. In the future, we plan to study in more detail exactly how different types of waves interact with charged particles in the Earth's magnetosphere," said Alexander Rubtsov, a researcher at the Institute of Physics of the Sun and Earth of the SB RAS in Irkutsk, whose words were quoted by the Russian Science Foundation's press service.

During the study, scientists examined data collected by Japan's ARASE spacecraft in Earth orbit from March 2017 to December 2020. The spacecraft was launched into space to study geomagnetic storms as well as the properties of Earth's magnetic field and associated radiation belts.

During its first four years in orbit, ARASE witnessed several bursts of solar activity and episodes of significant solar wind growth. Based on these data, the scientists investigated how the collision of the stream of charged particles emitted by the Sun affected the configuration and variations of the Earth's magnetic field at different altitudes from the planet's surface.

The analysis showed that low-frequency magnetic field fluctuations, caused by solar activity and potentially dangerous to orbiting probes, are present in the upper part of the Earth's magnetosphere but absent in its lower half, the plasma sphere, the region of space directly above the outer part of the Earth's atmosphere - the ionosphere.

The scientists' calculations show that low-frequency waves still affect the orbiting satellites during strong magnetic storms, even though these vibrations do not penetrate the plasma sphere. Scientists suggest that this is because these waves transfer their energy to charged particles inside the plasma sphere, which increases the level of radiation and makes it easier for these particles to penetrate near-Earth space. This must be taken into account when designing the probe's protection systems, the researchers concluded.

(TASS/USA)