The last few days have been packed with macroeconomic events and data. Some of the news came from the US, some from Europe. But interestingly, the two sets of data coincide in their main trends. For some time now, there has been data coming from both sides of the Atlantic that seem to confirm a minor, subtle stagflation. That is, a combination of stagnant or low economic growth and higher inflation at the same time.

It is not a big deal; neither GDP nor inflation are so extreme as to attract attention. But after all, economic growth is below the long-term normal and inflation is above the long-term normal. And that is exactly what has now been confirmed.

On Wednesday, consumer inflation statistics from the US showed that the annual rate of consumer price inflation accelerated to 2.7 percent in November. Then on Thursday came the news that US producer prices rose at an annual rate of 3.0 % in November, more than expected. But in contrast, new claims for US unemployment benefits in the week to December 7 came in at 242,000, which was more than expected. And the high number of unemployment benefits is a sure sign of slower than expected economic growth. The term "stagflation" would certainly be a strong word; we could only talk about stagflation if economic growth was zero. However, this is not the case here: It is far more common for accelerating economic growth to be accompanied by accelerating inflation, or for both to slow down simultaneously. But here the opposite is happening, both seemingly going against each other.

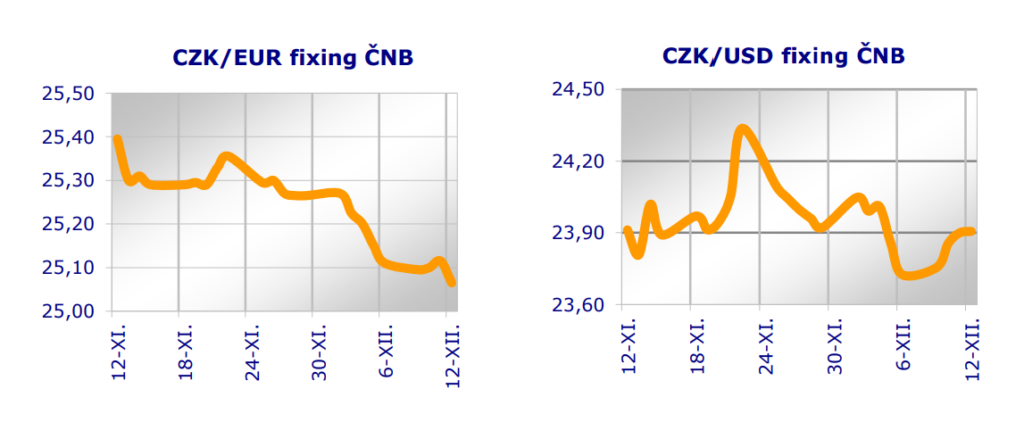

And the situation is similar in Europe. The inflation rate in the euro area only fell below the ECB's 2% target in September this year, for the first time since mid-2021. However, inflation rose again to two per cent in October, and in November it rose to 2.3 per cent, according to preliminary data. And no one doubts that eurozone economic growth is miserable. So, again, inflation is too high for such weak growth, or, conversely, the performance of the economy is too low for such high inflation.

And we can say exactly the same about the Czech Republic. Inflation of 2.8 percent is not a disaster, but it tends to rise slowly, and such relatively high inflation would be matched by much higher economic growth than the current one, which will probably pull it up to around 1 percent for the whole of 2024.

How is that possible? It's because most of that pent-up growth is bought with debt. The Biden administration has perpetrated historically record government spending. In the Czech economy, too, budget spending has been enormous under the Fial administration. In both of these economies, it can be estimated that economic growth would be close to stagnant if the government had not bought it with debt in this way. But at the same time, a side effect of this huge government spending in the economy is the high amount of money in circulation. And this high money supply causes - inflation.

In fact, this is best seen in the case of the eurozone and the European Central Bank (ECB). The latter has actually "cursed" by lowering its base interest rate. In fact, the ECB is cutting its main refinancing rate by 25 basis points to 3.15 %. It expects further cuts next year. She accompanied this with a series of words about how she said "the disinflation process is well on its way." Except that we just said a moment ago that inflation in the eurozone has instead risen in the last two months, so that's not true. But the ECB has its back against the wall. It has to cut interest rates, even if it does not want to, or else it will be hit badly by, for example, France, which is starting to have a huge problem with its budget deficit. With higher interest rates, it would not finance it. So the ECB has to print money into circulation. Again. And once again, it's fueling inflation.

And just as before the pandemic, this inflation is so far visible especially in the prices of securities and real estate. But this is only temporary.

Markéta Šichtařová

Eurodeník 12/12/2024 Next Finamce s.r.o. Nextfinance.cz

AUDIO form can be found here