"Now I want to open the book of the world before you. And there are no words in it, only beautiful pictures."

"I can't say why I wanted to paint. The only answer is in the paintings themselves."

"My plays are not didactic, they just express my attitude to the world."

"We have to pay for experience in life. If we're lucky, we get a discount."

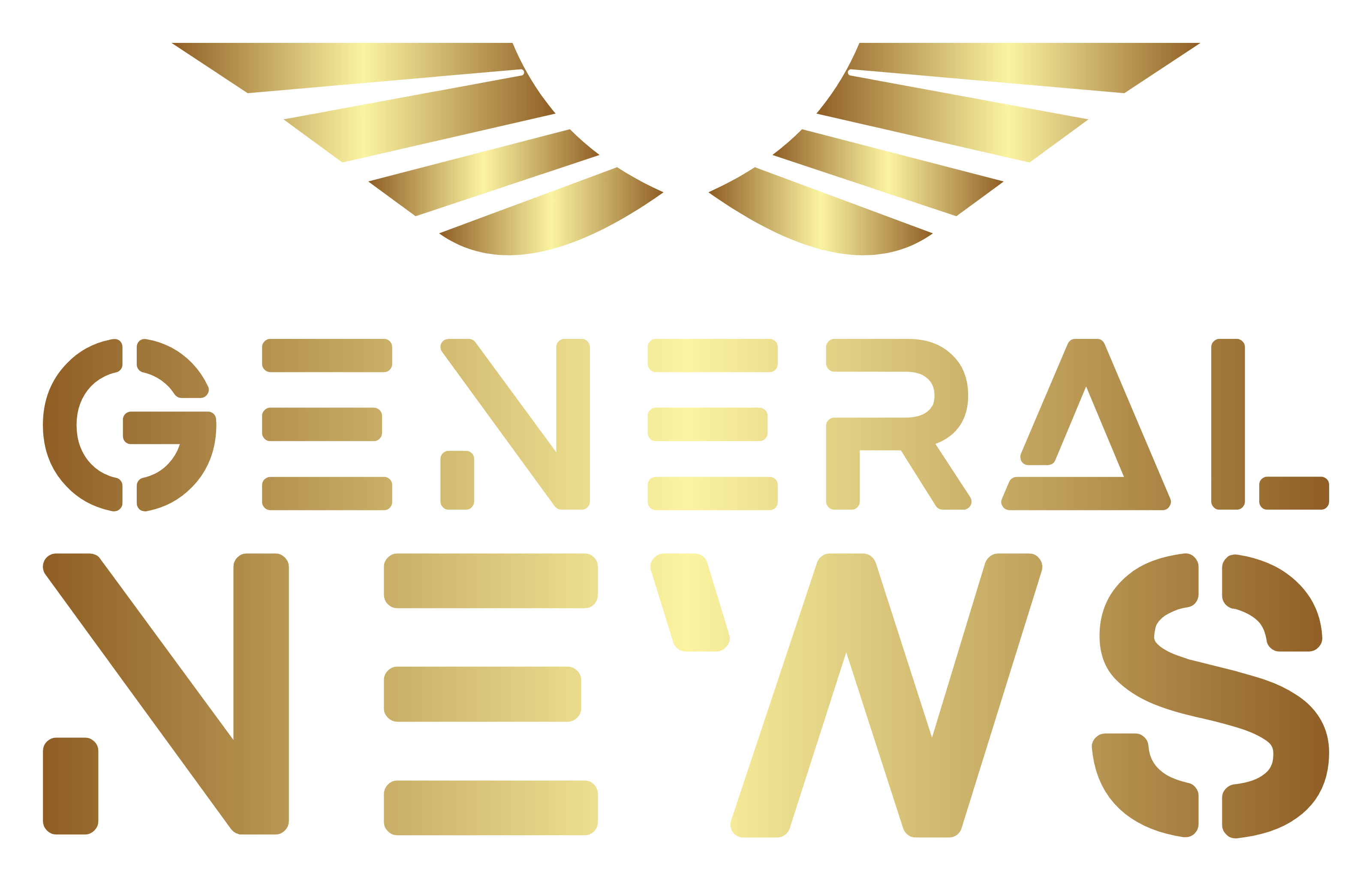

Austrian painter, illustrator and graphic designer, also poet and author of plays with Czech roots Oskar Kokoschka is one of the prominent figures of the Expressionist art movement. He is known for his extravagant portraits in which he tried to capture the emotions of his models, as well as his paintings of landscapes and cityscapes. In his time, his provocative work did not meet with much appreciation because he did not respect any rules, ignored the established norms of art and went his own way. He was labelled a degenerate artist by the Nazis. Today, his paintings hang in galleries around the world from New York to Tokyo and are among the most expensive at auction.

Oskar Kokoschka was born on 1 March 1886 in the Austrian town of Pöchlarn in the house of his maternal grandparents. His family home now serves as a museum. Every year, from May to October, exhibitions are held here, devoted, for example, to photographs, paintings of nature and illustrations of world literature.

Oskar was the second son of four children of the goldsmith Gustav Kokoschka and Maria Romana, née Loidl, daughter of a Styrian forester. The first-born Gustav died as a toddler, three years after Oskar was born Berta and in 1892 Bohuslav, whose name indicates that Czech traditions prevailed in the family. Grandfather Václav and Uncle Josef on his father's side were Prague goldsmiths, another uncle was a watchmaker. They owned the house U Ježíška with a shop in Spálená Street. Oskar's father also learned the goldsmith's craft in the family workshop, but the artistic craft was not successful in Prague at that time, so after his grandfather's untimely death he sold the shop and workshops and became a travelling salesman. Oskar was not yet a year old and the family settled in Vienna because of his father's work. However, they did not fare too well, moving several times to ever smaller and cheaper apartments in the suburbs. So when he started earning money, Oskar supported the family financially.

From childhood he strongly believed in omens and divination and was fascinated by fire. He was led there by a family story about a fire that broke out in Pöchlarn shortly after his mother brought him into the world. At that time, the fire destroyed almost the entire town, and his uncle's mill and grandfather's house were also burned down. The mother and her infant were saved by a quick departure on a high ladder with hay.

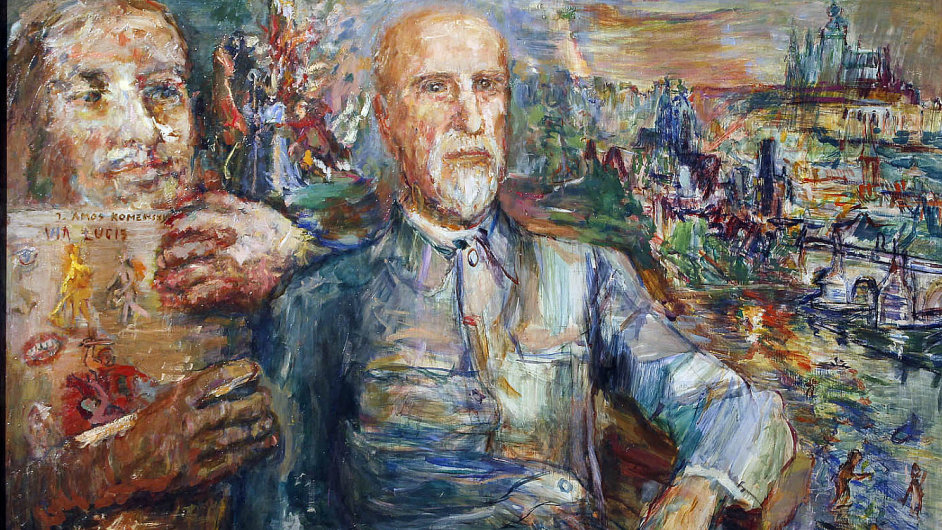

The fascination with fire and its symbolism was later reflected in some of Kokoschka's works. In his autobiography, for example, he mentions the fire of Rome as a historical event that inspired him to reflect on destruction and reconstruction. The same is true of the fire at Lesno, in which J. A. Komenský, for whom he had a deep admiration, lost the manuscripts on which he had worked practically all his life. Kokoschka often used fire motifs in his paintings to express intense emotions or dramatic changes.

In his childhood he was not particularly interested in art, he wanted to become a chemist and do experiments. In 1897 he entered the C. and K. State Real School, but he was not very interested in his studies. His earliest surviving drawings and watercolours date from that time, and one of his teachers took an interest in them and recommended him to take up painting. Oskar listened and against his father's wishes, in 1905 he enrolled at the Vienna School of Applied Arts, today's University of Applied Arts. He was one of the few applicants who were accepted and received a scholarship. The school focused mainly on graphic techniques, architecture, furniture, crafts and modern design and, unlike the more prestigious and traditional Academy of Fine Arts, it was staffed by teachers from the Viennese Art Nouveau movement. One of them was Gustav Klimt, whose work strongly influenced Oskar. He was also greatly influenced by the Viennese painter Rudolf Kalvach and especially Vincent van Gogh. During his studies he became friends with the architect Adolf Loos and later, under his influence, he rejected Art Nouveau, which was still prevalent at the time, and became a pioneer of Expressionism.

Through his teachers, Kokoschka established cooperation with the so-called Vienna Art Workshops, a society founded in 1903 to promote arts and crafts, and there he published his first series of eight colour lithographs to accompany his ecstatic poem in 1906-1908 Dreaming boys. Today it is often cited as one of the basic works of Expressionism, not only in its literary aspect, but also in its artistic aspect.

Kokoschka's first recognition came from portraits of Viennese celebrities, but his main commissions at the time were postcards and drawings for children. In addition to painting, he was also involved in literature, writing poems, essays and plays. In 1908 he made his debut with the scandalous drama Killer, the hope of womenfor which he created the poster himself, directed it and performed it in the Garden Theatre at the Kunstschau Wien exhibition of arts and crafts organised by Gustav Klimt and a group of avant-garde artists.

The Viennese society of the time did not understand his play and did not accept it. In protest against the insults he received from the press, Kokoschka had his hair cut and painted self-portraits with the appearance of an intellectual prisoner, punished for his innovative ideas. In the same year, he was expelled from the School of Arts and Crafts, because such a "disruptive element" as himself could not naturally remain there. The constant criticism eventually became the best advertisement for him.

He finished his Viennese studies and after a short stay in Switzerland in 1910 accepted the invitation of the gallerist and publisher Herwarth Walden and settled in Berlin, where he began to collaborate with his newly founded avant-garde literary magazine Der Sturm. In 1912, he had a solo exhibition in the gallery of the same name, he also exhibited there together with Otakar Kubín.

In 1911 Kokoschka returned to Vienna and embarked on a career as a teacher. He was offered a teaching position at his former alma mater, from which he had previously been expelled. In April 2012 he met Alma Mahler, seven years his senior, the beautiful widow of the famous composer Gustav Mahler and hostess of one of Vienna's most frequented intellectual salons, who had lost not only her husband but also her four-year-old daughter Maria shortly before. He began a passionate love affair with her.

After a few months together, Alma became pregnant, but she had the child taken away and refused to marry. Kokoschka later admitted that the loss of the child hurt him and often said that he painted so much only because he had no children. The tempestuous relationship lasted two years, but then fell apart, the painter being too possessive and jealous for the independent Alma. When she broke up with him on New Year's Eve 1914, Kokoschka sold the painting Bride of the Windwhich he painted during their stay together in Naples in her honour, bought a horse and armour with it, volunteered to join a dragoon regiment of the Austrian army and went to fight in the First World War. All this, among other things, because she told him in an argument that he was a coward.

In 1915, Alma married the German architect Walter Gropius, while Oskar was severely wounded on the head in Halych, left on the battlefield and a soldier even tried to finish him off with a bayonet and punctured his lung. Fortunately he survived and after a medical stay in Vienna, he was sent to the Eastern Front near Sochi in 1916, where he served as a war painter, but was again wounded in a bridge explosion. He went to Stockholm to seek the help of a doctor specializing in brain injuries, then made his way to Dresden. His war experiences made him a lifelong avowed pacifist.

He felt so psychologically down that in 1918, as part of his therapy, he had a life-size doll made in Munich based on Alma, which he treated as if it were alive... He kept it as his muse until 1922, when he symbolically cut off its head, thus ending his obsession with Alma. In the 10 years since they met, he wrote her 400 letters, painted several oil paintings and countless drawings. His relationship with her also inspired his poem Allos Markar.

He finished his drama in Dresden Job with fourteen illustrative lithographs, and from 1919 to 1923 he was a professor at the Dresden Academy of Arts.

In addition to teaching art, he wrote articles and speeches documenting his views and practices as an educator. He was influenced by the aforementioned Czech humanist and educational reformer, the "teacher of nations" Jan Amos Komenský, who lived in the 17th century. Kokoschka's grandfather Václav was also an admirer of Comenius and applied his pedagogical principles in the education of his children, which was passed on to his grandson.

Comenius' book Orbis pictus Oskar received as a child for Christmas and, as he later wrote in his autobiography My life, opened up a new world of knowledge and accompanied him throughout his life, influencing his decision to become a painter and later a defender of Comenius' ideas: "Orbis pictus taught me what the world is like and what it should be like for people to live in it." From Comenius he took the view that students benefit from using their five senses in learning. He was convinced that "seeing with one's own eyes" was a prerequisite for artistic creativity. He therefore disregarded traditional methods and taught by telling stories full of mythological themes and dramatic emotions.

After leaving Dresden, he settled in Paris. In the following years he travelled in Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. Many landscape and cityscape paintings were produced there, as well as portraits of famous people he met. By this time he was already enjoying considerable artistic success and his work was becoming known to a wider public.

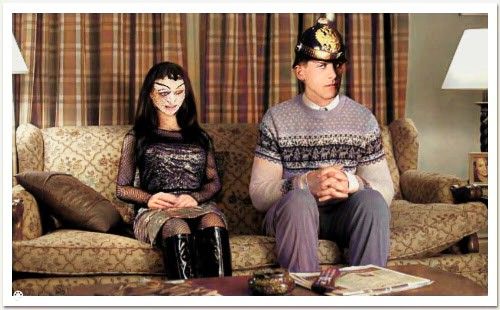

In 1933 he left Paris and returned briefly to Vienna, where he settled in the house he had bought for his parents years before. The political situation in Germany and a premonition of developments in Austria, as well as the death of his mother, forced Kokoschka to move to Prague in September 1934, where his sister Berta Patočková-Kokoschková had lived since 1919. It was she who invited her brother to Bohemia.

Kokoschka was not an unknown artist in Prague. As early as December 1933, the picture dealer Hugo Feigl arranged a successful exhibition for him at his gallery on Smetana Embankment and upon his arrival arranged most of his commissions. Their walks through the city resulted in 16 expressionist paintings of Prague.

After Feigl introduced Kokoschka to President T. G. Masaryk, a portrait of the president was created. In 1944, Feigl arranged for the sale of Masaryk's portrait to Pittsburgh and the proceeds were used to support Czechoslovak war orphans.

But Kokoschka didn't just paint Hradcany and portraits; along with Picasso, he was the most famous of the modern artists who expressed their opposition when the German air force bombed the Basque town of Guernica in Spain on 26 April 1937. Kokoschka created a poster Help the Basque children!, which was put up in Prague by students overnight and torn down by Prague police during the day because of the threatened diplomatic rift with Germany. Kokoschka later recalled that the Nazis threatened him on radio broadcasts: "When we get to Prague, you'll be hanging from the first lantern!" And it didn't stop there. In 1937, a purge was carried out in German museums and galleries in an attempt to get rid of paintings and sculptures that Hitler and his henchmen described as degenerate creations of the psyche of deranged artists of a Judeo-Bolshevik orientation. Kokoschka, who had many enthusiastic collectors in Germany but was declared a "degenerate" and "degenerate" artist by the Nazis, was also on the list of 18 banned artists. In total, 28 of his paintings and several hundred prints and drawings were confiscated.

At the end of 1937 Kokoschka had kidney problems and was hospitalized in North Moravia for several weeks. During his stay with friends in Vítkovice, he made a likeness which he provocatively called Self-portrait of a perverted artist.

At the same time, he initiated the Oskar-Kokoschka-Bund, chaired by Theo Balden, which sought to create art independent of the Nazi aesthetic that branded his paintings as degenerate art.

In Prague in the autumn of 1934 Kokoschka met a nineteen-year-old law student Oldřiška (Olda) Palkovská, the daughter of the lawyer and art collector Karel B. Palkovský. To the dismay of his parents, he began seeing her and also painted her several times. The age difference between them was 29 years. Palkovský sent his daughter first to Paris and then to London to "cure" her love for the painter, but to no avail.

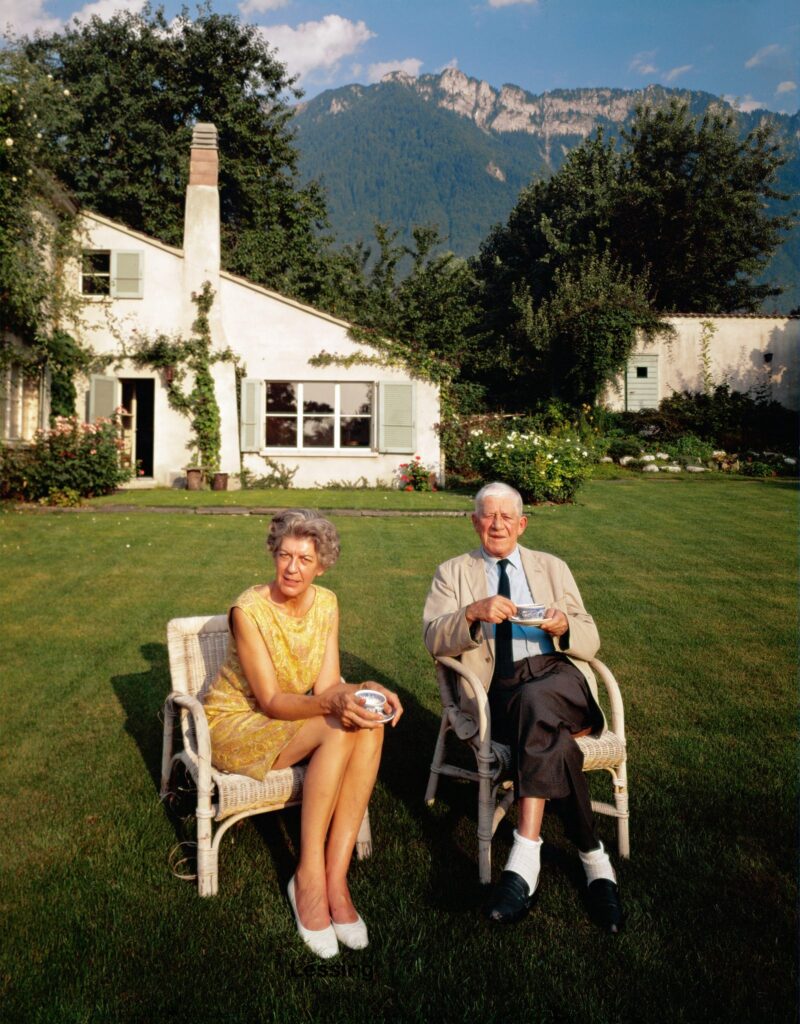

In July 1938 Kokoschka was granted Czechoslovak citizenship. But then came the Munich dictate and the Germans began their occupation of the Sudetenland. As a convinced anti-fascist, Kokoschka flew to London in October 1938, where he and Olga were married in 1941 in an air-raid shelter.

During this time he painted two paintings - Red eggs (1940), which is now on display at the National Gallery in Prague, and the painting Connections - Alice in Wonderland (1942). He donated the proceeds from their sale to the Free Austrian Movement. He and Olga spent the 1940s in England, and in early 1947 both became British citizens. After a short stay in the USA, they lived in Switzerland from 1953, where the first major post-war Kokoschka exhibitions were held in Zurich and Basel.

Although Kokoschka was an anti-fascist, in 1966 he painted a portrait of the first post-war German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, which later hung in Angela Merkel's office. It was not until 1975 that he took back his Austrian citizenship, but he never left Switzerland.

He and Olga settled permanently in the Swiss village of Villeneuve on the shores of Lake Geneva, where they bought a house called Villa Delphin.

From there Kokoschka travelled regularly to Salzburg, Austria, from 1953 to 1962, where he taught courses as part of the International Summer Academy of Fine Arts. School of Vision, again based on the principles of the educational method of J. A. Comenius. The personality and life of the "teacher of nations" fascinated him so much that in the 1930s he wrote a drama about his life called Comenius. The play was then produced in Hamburg in the 1970s, made into a film, and a graphic cycle in colour serigraphy was produced (1976), distributed in large numbers as a collector's album.

Almost daily, Kokoschka spent time in the garden of his villa in Villeneuve, painting vibrant watercolours of floral still lifes, some of which became the subjects of lithographs.

He also made numerous trips to European and non-European countries and held various retrospective exhibitions of his work in Switzerland, Austria and Japan. He lived and worked in his studio in Villeneuve until late in life. In 1971, his autobiography entitled Mein Lebenin 1984, after his death, then his correspondence.

The internationally acclaimed artist died on 22 February 1980 in Montreux from complications after contracting influenza, eight days before his 94th birthday. He was buried in the cemetery in Montreaux's Clarens district. After his death, the Oskar Kokoschka Prize for Achievement in the Visual Arts was established.

Wikipedia/ Facebook/ Gnews.cz - Jana Černá