Sorge: "If anyone is going to destroy Hitler, it's me!"

For the work of a secret agent, he was Richard Sorge ...just right. Extremely intelligent, educated, a charming lover of gambling, women and alcohol, crazy about motorbikes, a talent for languages - besides his native German and Russian, he also knew English, French, Japanese and Chinese. The man who got every woman into bed and managed to coax secrets out of every man, a master of manipulation and disinformation, was executed in Japan eighty years ago.

In his own words, he did not want a career as a spy, he did it to prevent war. He hated the war because he had experienced firsthand the hell in the trenches.

The most successful spy of all time brought secret information out of the highest circles of the German and Japanese military command for almost nine years and significantly influenced the course of the Second World War.

Thanks to his information that Japan would not attack the Soviet Union, Stalin withdrew his troops from Siberia to the west and pushed back the advancing Wehrmacht in the winter of 1941: a blow from which Hitler's Germany never recovered. Sorge had warned Stalin several times before about "Operation Barbarossa", but he initially ignored the reports, believing more in the Ribbentrop-Molotov Non-Aggression Pact.

The future famous agent was born on October 4, 1895 in Baku in present-day Azerbaijan, the youngest of nine children of Wilhelm Sorge, a German mining engineer working for an oil company, and his Russian wife Nina Semyonovna Kobeleva.

When Richard was three years old, his father's work contract ended and the family returned to Germany, settling in Berlin. When he was nineteen, the First World War began and he enlisted in the German army. At that time he still subscribed to the right-wing nationalism that his father had espoused. But the war experience changed him.

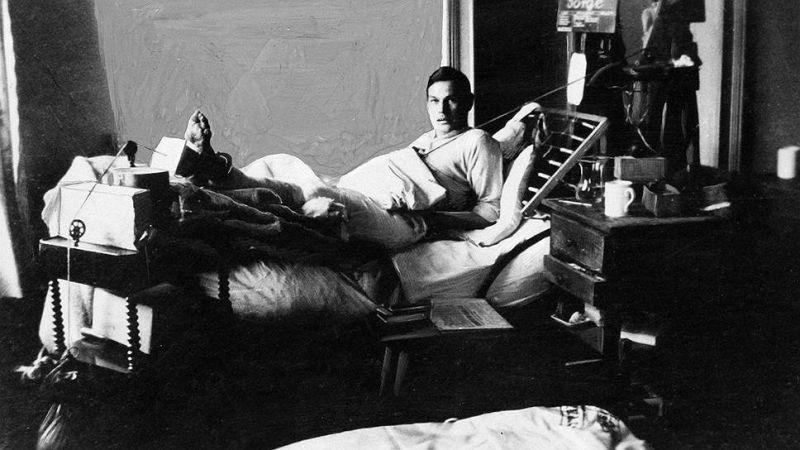

He was severely wounded several times at the front; in 1917, shrapnel tore off three of his fingers and injured both legs so that he was lame for the rest of his life. He was awarded the Iron Cross for his heroism and during his convalescence he read the books of Karl Marx and became a communist. After all, it ran in the family, his great-uncle Friedrich Adolf Sorge was Karl Marx's private secretary and general secretary of the First International.

Sorge spent the rest of the war studying philosophy and economics at the universities of Kiel, Berlin and Hamburg. In 1919 he received a doctorate in political science in Hamburg, joined the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) and became editor of the party newspaper in Solingen. In 1921, he married Christiane Gerlach, 18 years his senior, the wife of his political science professor from Kiel and Communist Kurt Gerlach, who divorced him.

After three years they moved to Moscow. Sorge joined the CPSU in 1925 and obtained Soviet citizenship. He worked for the intelligence department for five years, responsible for gathering intelligence and building a network of informants. He became a favorite companion of officers and their wives, which was hard on his wife, who knew nothing of his espionage work. By 1926 she had returned to Germany and they divorced in 1932.

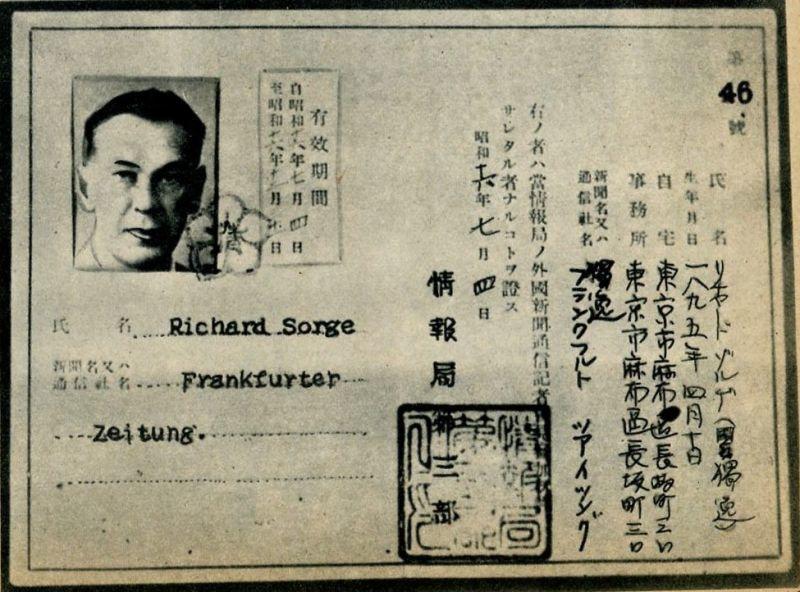

In 1930, Sorge was sent to Shanghai to help in the attempt to start a communist revolution in China. He took a job as editor of the Frankfurter Zeitung. As a journalist, he established himself as an expert on Chinese agriculture. In this role he travelled around the country and contacted members of the Chinese Communist Party. His articles eventually opened the way to Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek himself.

In Shanghai, Sorge met the Japanese journalist Hatzumi Ozaki and during nightly strolls through brothels and bars, the two became inseparable friends. Ozaki was a graduate of Tokyo's prestigious Imperial University, had access to high political circles and rejected Japanese imperial policies. In late 1932, both Sorge and Ozaki left Shanghai.

Sorge was recalled to Moscow and on his return wrote a book on Chinese agriculture. He also married a second time to Ekaterina Maximova, whom he had met in China and brought with him to Russia. The marriage was formal and ended with her death in 1943. She was accused of being a "German spy" as the wife of a German citizen and deported to the Gulag, where she died.

In 1933, Sorge went to Berlin to renew old contacts and secure a cover identity. He obtained a position as correspondent for the Zeitschrift für Geopolitik, founded by a personal friend of Rudolf Hess, and through his intercession was accepted into the NSDAP. He soon penetrated its highest circles, preferring to stop drinking so as not to swear during joint binges.

He went to Japan with so many letters of recommendation that the German community in Tokyo welcomed him with open arms. He played his part perfectly. Within a few months he was fluent in Japanese and familiar with the local etiquette. Invitations to parties at embassies and drinking parties at military clubs poured in. Colonel Eugen Ott, the German military attaché and later ambassador to Japan, took a liking to the charming young Nazi, as did his wife, who was Sorge's mistress. In 1939 Sorge became press attaché at the German embassy, which gave him access to confidential material and information.

He gradually built up a spy ring of about 40 people, infiltrating not only the German elite but also Japanese politicians and military officers. Among his associates was Ozaki.

A few weeks in advance, Sorge informed Moscow of the German attack planned for the summer of 1941, which Stalin unfortunately did not believe. Thanks to Ozaki, who had access to the results of a meeting of the top Japanese leadership, Sorge was able to send another dispatch to Moscow in September 1941 that a Japanese attack in the northern direction would not take place: Japan would not attack Siberia, but Indochina. Stalin already believed this, reassigned 34 divisions from the Far East to Moscow and put Marshal Zhukov in charge of its defence. With these reinforcements, the Red Army halted the German advance on Moscow in December 1941.

Sorge also reported on the preparations of the Japanese fleet including aircraft carriers to attack Pearl Harbor, although he could not yet give an exact date. But by that time, his group's fate was sealed.

In early October 1941, one of Sorge's associates was accidentally arrested. During interrogation he attempted suicide by jumping through a window, but only broke his leg. Then he collapsed and testified. Arrests of members of the group followed, and eventually of Sorge. After many interrogations, he decided to write a confession. We can hardly be under any illusions about what preceded it. In 1943, Sorge was sentenced to death by hanging and his friend Ozaki was sentenced to the same. He was executed at Sugamo Prison on 7 November 1944, on the anniversary of the Great Patriotic War.

The Japanese claim that in Sorge's case they offered Moscow a trade, but it did not respond. But it is questionable whether this would have been possible in a situation where Germany was still a Japanese ally.

Many women passed through Sorge's life, the last of whom was his faithful geisha Hanako Ishia (Flower Girl), whom he had been seeing since October 1935. Hanako was not among the accused and eventually recovered Sorge's remains from a mass grave. Before being cremated, she allegedly had his gold crowns made into a ring, which she never removed for the rest of her life. She also arranged for his burial in Tokyo's Tama Cemetery and had an inscription engraved on his tombstone: "Here lies a hero who gave his life in the fight against war and for world peace."

In 1964, Richard Sorge was awarded the title Hero of the Soviet Union in memoriam for his merits and courage.

A year later, Hanako was invited to Yalta and received a pension as the widow of a war hero.

Facebook / wikipedia / gnews.cz - Jana Černá