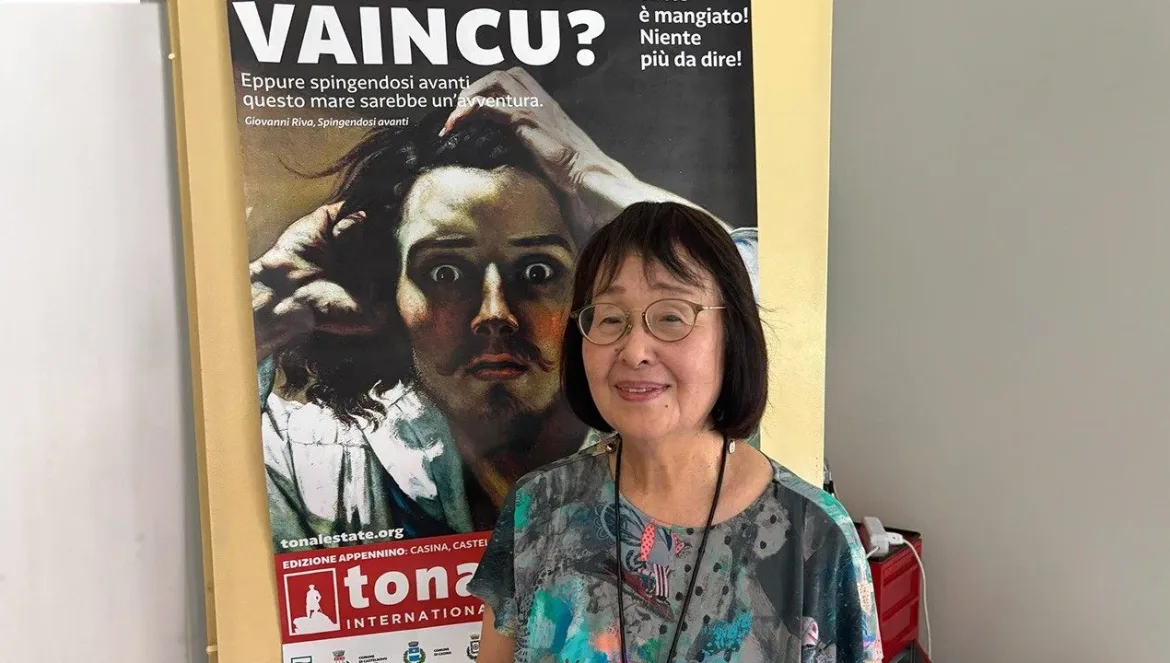

Michiko Kono talks to Vatican News about her life as an atomic bomb survivor, 79 years after Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Michiko was only four months old on August 6, 1945. On that day 79 years ago, an American B-29 fighter plane dropped an atomic bomb, known as "Little Boy," over her hometown of Hiroshima.

It was 8:15 a.m. and Michiko was with her parents at Hiroshima Station, where her mother had just put her on a wooden bench to change her.

Shortly thereafter, just two kilometres away and at an altitude of two thousand metres, the "Little Boy" atomic bomb was detonated. 80,000 people died on the spot. The heat from the blast hit the station, and although her parents suffered severe burns, Michiko was lucky on the wooden bench - the backrest protected her from the heat and she suffered no injuries. One mile south, in their house, her grandmother was widowed.

Because Michiko was only four months old at the time, she has no memory of the event, but she knows what it is like to spend a lifetime as a survivor dedicated to spreading a message of peace and hope to younger generations.

Her voice perfectly matches that of Pope Francis, who visited the bomb sites in Hiroshima and Nagasaki - bombed just three days after Hiroshima.

Following the example of his predecessor John Paul II, who visited the sites in 1989, Pope Francis stood at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial thirty years later and delivered a historic speech in which he condemned the use and possession of atomic weapons as "immoral".

On that occasion, the Pope stressed that "the use of atomic energy for war purposes is today more than ever a crime not only against the dignity of human beings but also against any possible future for our common home. The use of atomic energy for war purposes is immoral, just as the possession of atomic weapons is immoral", and then warned, "For this we will be judged."

Childhood in the shadow of the bomb

The Hiroshima Peace Museum, visited by Pope Francis and where Michiko Kono now volunteers, opened in 1955, ten years after the bomb exploded.

It took her 40 years to find the courage to visit the museum. "My mother took me there when I was 10 years old, but I was afraid to go in," she says. In 2001, "I realized that it was my duty as a survivor to tell my story."

It was only at the museum that she realized how lucky she was.

"When I was a child I lived in the suburbs of Hiroshima and went to school there. There I didn't see the effects of radiation so much. From the museum, I learned about its effects and about the children who died in elementary school from leukemia and other diseases caused by the bomb."

350,000 people lived in the city and by the end of the year 140,000 had died. More than half of the dead were immediately turned into unidentifiable ashes that now lie in the crypt of the memorial.

Many people have suffered from the effects of radiation exposure. Many of them died, and many others are still suffering from the effects of radiation.

In 2005, Michiko joined the successor system of the Hiroshima Museum. There she met Mitsuo Kodama, with whom she spoke and learned from for two years. He was 16 years old at the time of the atomic bomb explosion and lived with the severe effects of radiation exposure until his death at the age of 66. Now Mrs. Kono travels the world telling his story and legacy.

Side effects?

Although Michiko Kono and her family were among the happier ones, Michiko had some strange experiences while growing up.

"In June, a year after the explosion, I fell ill with high fever and diarrhea. My doctor thought I was going to die. My father suffered from bleeding gums for some time after the explosion, while my mother had a constant low fever. I remember when I was about nine years old, many boils appeared on my lower body. They hurt a lot. To this day, she says, I don't know what caused them. "Then when I was a teenager in high school, I suffered from summer exhaustion. That, too, could have been a result of radiation. And when I was in college, my fingers would sometimes swell when I was tired. I always wondered if it was the radiation."

But Michiko doesn't know if it was the radiation, nor does she know if the others were experiencing strange things they couldn't explain. "At the time, there was no information about the effects of radiation. It wasn't commonly talked about in the media, so we didn't notice and couldn't compare."

In the years after the war, Japan was occupied by the Allies, led by the United States. For seven years, until the end of the occupation in 1951, there were restrictions on media coverage and information and research materials related to the atomic bomb.

Every citizen of the world should know

Now, Ms Kono says, "I think more people are starting to learn about the atomic bomb". She talks of world leaders visiting the Hiroshima Peace Museum and learning "how powerful and terrible the atomic bomb was".

But this is not enough, he continues, "Every citizen of the world should know how cruel the atomic bomb was".

His message to young people is: " Come to Hiroshima and Nagasaki and see how terrible and cruel the atomic bomb was. Start thinking about the possibility of ending nuclear weapons."

This, he concludes, "is essential for a peaceful world".

gnews.cz/Francesca Merlo - Vatican News